There are two true types of survey questions; objective questions and subjective questions.

Objective questions

Objective questions are those based in fact, where a respondent’s answer can be determined as right, wrong, true or false. An example of an objective question would be to ask where someone lives or what they bought from your store.

Subjective questions

Subjective questions aim to measure a respondent’s feelings, attitudes and perceptions of something. For example, how they felt about the quality of customer service or what their favourite brand of coffee is.

The style of question you choose to employ in your online survey will largely depend on what your overall goals are. If you’re running a health survey, most of your questions will concern a respondent’s exercise and dietary routes, and be mostly objective.

If you were asking pre-event survey questions, a large majority of them would concern your attendee’s expectations and needs, and would therefore be subjective.

It’s likely you’ll use both forms of questions in your survey for a complete account of your respondent’s experience.

Whichever form you stick to in your survey will also impact the question types you employ.

Types of survey questions

When it comes to surveys, there are 8 main question types:

What type of question you choose, and how you ask that question, can determine the quality of data you collect from respondents.

If you’d like to learn more about each of these types, their strengths and the best tips we have for writing the perfect survey question, read on.

Open ended questions

Open ended questions are used to collect qualitative data, which is more in-depth and meaningful. Respondents are given to space to provide detail and often work well in tandem with close ended questions, where they can explain previous answer choices.

However, because the responses are more long-form, the data can be time consuming to analyze.

Open ended question examples

- What is it like to live in the United States?

- How was your meal?

- What was the most memorable aspect of the festival?

Close ended questions

These types of questions only require a one-word answer, like yes or no. They’re useful for collecting quantitative sets of data, where you’re looking for some statistical significance in the results.

They can also be used to learn about your respondents or to test their knowledge on a subject.

Closed ended question examples

- Do you live in the UK?

- Can you ride a bike?

- Is the sky blue?

Rating questions

Rating scale questions are a great tool for measuring attitudes and opinions of your respondents. You could ask them to what extent do they agree with a statement or to assign a star rating to a movie or restaurant.

This question type can also be used to determine your Net Promoter Score (customer loyalty).

Rating question examples

- How likely are you to recommend our product/service to a friend?

- Please, rate our restaurant out of 5 stars.

- Overall, how happy were you with the event?

Ranking questions

Ask respondents to rank a set of options from first to last based on a factor you’ve set. For instance, you could require that soda brands be ranked based on their taste.

Each answer position will assign an answer option a weight and the average weight of each result will be indicated in your results.

Ranking question example

Rank the following aspects of the store in order of importance from 1 to 5 where 1 is most important to you and 5 is least important to you:

- Cleanliness

- Parking access

- Availability of staff

- Product range

- Pricing

Likert scale (matrix questions)

Like rating questions, Likert scales are useful for measuring how people feel about something. These are more commonly used to rate people’s experiences, such as how satisfied they were with customer service.

However, they more commonly employ a 5, 7 or 9 point scale, where rating questions usually measure on a scale of 5 or 10.

Likert scale example

- How satisfied were you with the quality of learning materials?

- Do you agree that today’s event was a success?

- How important do you feel this afternoon’s meeting agenda was?

Multiple choice questions

Here’s where you’ll provide a set list of answer choices for respondents to pick from. They work best when you have an exhaustive list of answers, such as you would for a quiz.

You can set these question types to accept a single answer or set a limit for multiple answers to be chosen.

Multiple choice question examples

- Which is the largest city in the UK?

A: Edinburgh | B: Manchester | C: London | D: Liverpool - What is the square root of 9?

A: 5 | B: 3 | C: 6 | D: 1 - How much is a baker’s dozen?

A: 10| B: 11 | C:12 | D:13

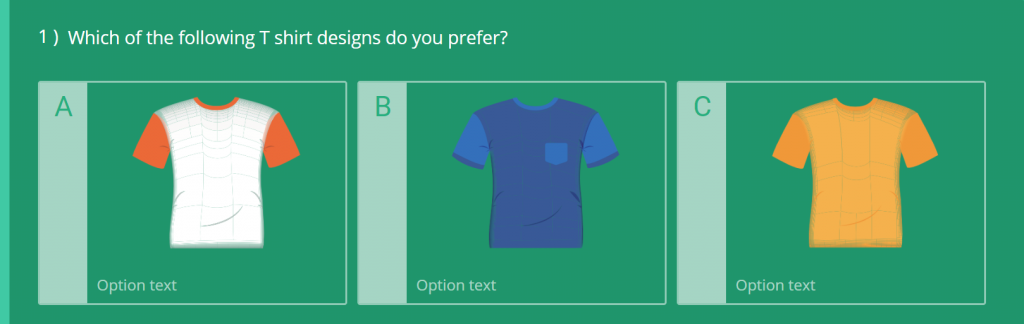

Picture choice questions

To keep respondents engaged, all surveys should strive to be as visually appealing to as possible. Picture choice question types make your survey that little bit more interactive and allow a little reprieve from reading bulks of text.

It also makes testing product and logo concepts easier in market research surveys.

Picture choice question example

Demographic questions

These types of survey questions regard personal or sensitive information about the respondent, e.g. age, income, religious beliefs.

They are the most difficult question types to master and respondents can react to them in so many ways depending on how you ask and where in the survey you ask them (or whether they feel it’s necessary for you to ask them at all).

Demographic questions can be both open and close ended. If you’re using open ended text fields you run the risk of input errors, which may slow down the analysis of your results.

If you use close ended questions, then you run the risk of your answers selection not being exhaustive.

Demographic question examples

- Which gender do you identify as?

- What is your annual household income?

- To which age group do you belong?

Mistakes made when writing survey questions

1. Writing leading questions

Leading questions are those written, intentionally or not, with emotional or persuasive language that influence a respondent’s answer choice.

To reduce the occurrence of bias in your data, you should ensure your question language and phrasing is as neutral as possible.

Bad Question: Do you have any concerns about the training program so far.

The wording in this question example only asks the respondent to think about the concerns, or negative aspects, of the course son far.

Instead, you should ask them to about their overall experience.

Good survey question: How would you describe your experience on the course so far?

2. Failing to provide mutually exclusive or exhaustive answer choices

When writing survey answers for multiple choice question types, you must ensure they don’t create an ambiguity for respondents.

The two most common occurrences of this are when answer options aren’t exhaustive or mutually exclusive.

Answer options that aren’t mutually exclusive:

- What is your age?

A: 18-25 | B: 25-35 | C: 35-45 | D: 45-55 | E: 55-65

In the above example, respondents wouldn’t know which age range to select if they were 25, 35, 45 or 55.

Each answer choice should be clearly discernible from all other options.

Answer options that aren’t exhaustive:

- By which method do you get to work?

A: Car | B: Train | C: Bus

An answer set that isn’t exhaustive doesn’t provide respondents with all the answers they’d expect for a question. Although three of the main modes of transport are included in the example, the question has not considered respondents who walk to work (or take use any other mode of transport).

Additionally, respondents may want to differentiate between driving themselves to work and carpooling with a colleague. To identify any answers you might be missing, carry out a test run of your survey with some colleagues or friends.

Provide an ‘Other’ answer option for each question and inspect your results for the most frequently occurring custom answers. Then you’ll have a good idea of the answer options respondents will expect for your question.

3. Asking indirect questions

Asking a question that’s too vague will lead to frustration in respondents. They want to answer each question proficiently and in as little time as possible.

Questions that aren’t specific enough, or ask respondents to consider too much, will lead to disengagement and even drop outs.

Either way, your results are likely to be affected.

Indirect question example:

- What do you do in your spare time?

Questions like this are bound to cause issues for respondents simply because they ask too much. For instance, what is meant by spare time? Is it time away from work or time spent alone?

Furthermore, what is the time frame? No one does the same thing with their spare time consistently, so where’s the limit to what a respondent can and can’t include.

4. Double barrelled questions

Asking more than one question at a time is likely to confuse respondents and will make your survey seem rushed and unrefined. On top of this, any results you collect for that question will be all but useless, as you won’t know which question a respondent was answering.

Divide double barrelled questions into two or remove the less important question from the survey altogether.

Double barrelled question example:

- Are your co-workers friendly and hardworking?

This question is assuming that all co-workers who’re friendly are also hardworking, and vice versa. Whereas a respondent may believe their co-workers only posses one of those traits.

In this same vein, you should also avoid writing double barrelled answer options.

Double barrelled answer option example:

- What is the best thing about working for this company?

A: Fair wages

B: Job benefits (e.g. free gym membership)

C: Friendly and hardworking co-workers

D: Well-designed office space

5. Unnecessary questions

You may try to get as much information out of your respondent as possible while you have their attention. But this tactic if often not worth the risk, as it’s something respondents are often aware of and they don’t tend react well.

Think about it, they’ve have chosen to invest their time and effort into your survey because they’re invested in the research of there’s some incentive on offer.

They’re happy to give the information they expect to, but then discover you’re asking questions unrelated to the research (for example, what their email address is).

Only include questions that contribute to meeting your research goals. You’re much more likely to have a higher response rate and won’t deter respondents from filling out any of your future surveys.

6. "What if..." questions

It’s best to avoid types of questions that propose a “what if” scenario, because people aren’t very good at predicting how they’d react to hypothetical situations.

The data you collect isn’t likely to be accurate and shouldn’t be used for any decision-making purposes.

Only ask questions that concerns a respondent’s actual experiences and always offer an opt-out answer option (such as N/A or “Other”) for those your question may not concern.

This would be a good opportunity to use page logic to direct respondents to pages that only concern them.

7. Asking questions people can't answer

Relying on a participant’s long-term memory is a sure-fire way to produce inaccurate results.

For example, if you’re running a customer satisfaction survey you may want to ask how a respondent’s last experience in your store was. If their last visit happened to be 8 months ago, you’re not going to get an answer that’s truly representative of that experience.

Only ask about events that have occurred recently or do so frequently.

8. Sensitive or taboo subjects

There’s a tendency in respondents to answer sensitive questions in a way that would be perceived as more socially acceptable, this is known as social desirability bias.

It often leads to over-reporting good behaviours (e.g. how often they exercise) and under-reporting bad behaviours (e.g. how many units of alcohol are consumed a week).

To combat this form of response bias, you could provide a short prelude to each question or page and make it clear that you’re collecting anonymous feedback.

Either of these methods can decrease the occurrence of social desirability bias and improve the quality of your results.

9. Asking ambiguous questions

Respondents shouldn’t have to think too hard about their answers. If you haven’t made the meaning of a question clear, then people are likely to guess at an answer or drop out of your survey.

To avoid creating ambiguity, you could provide extra information to define a term or the context of a question to assist them with their answer choice.

Ambiguous question examples:

- Where do you like to shop?

- How many times have you been to our store in the past month?

These examples are both too vague for a respondent to answer accurately. The first question does not define what kind of shopping is being asked about, e.g. food shopping or clothes shopping.

It also fails to provide a time frame, which is essential for a question like this as a respondent’s preference in shopping destinations will change over time.

The second example does provide a time frame but isn’t specific enough. Does “past month” mean the last 30 days or the current calendar month?

Too avoid ambiguity, always provide as many specifics in the question for a respondent to make informed choice.

Tips for how to write survey questions

1. Define your objective and stick to it

The purpose of your survey shouldn’t be to gather as much data on respondents as possible, but rather to use collect relevant data to achieve an objective.

This could be to inform academic research or improve your products or services, but the questions you ask should only aid in meeting that objective.

Respondents will know if you’re just digging for data and are likely to disengage or drop out when they do realise.

To ensure you stick to your objective, provide a statement at start of your survey defining your objective and how the data collected is essential to meeting it.

By doing this, also reduce the rate of answer dishonesty in your survey, as respondents will feel invested in your research because they’ll feel they’re providing something valuable to it.

2. Write clear and concise questions

When a question is too long, it’s often asking too much from a respondent. Keeping them as short as possible, whilst providing all the context they need to answer, is the key to collecting good quality survey data and keeping respondents engaged.

Information that’s essential for providing context questions are factors such as times, dates, locations, events and people. The more specific a question is, the easier it is for a respondent to an accurate answer.

3. Check for spelling and grammatical errors

If you want your participants to take your research seriously, make sure your survey content is written well.

A poorly written surveys will be jarring for respondents and is likely to cause disengagement, which leads to drops outs or answer dishonesty. Both of which are bad news for your results.

4. Use language that's universally understood

It’s important to reduce the occurrence of complex terms or jargon in your surveys, especially if it’s being shared to a wide audience.

For example, when running a market research survey, you should avoid using industry acronyms or jargon as your customers are unlikely to understand it. Similarly, if you’re running an academic research survey, your participants won’t understand subject specific terms.

If the terminology is essential to your questions or objective, then you should provide a definition at the start of your survey or above the question the term is used in.

5. Start with easy questions

To get your respondents to engage with your survey, place your simplest or most interesting questions at the beginning.

This will ease participants into your line of questioning and once they start, they’re more likely to see it through to the end. But if you place a tough question first, they may take one look at it and drop out.

6. Don't start with sensitive or demographic questions

Starting your survey with demographic questions, or others of a sensitive nature, will put a lot of respondents off. People are protective of data directly concerning them and are resistant to handing this information over to someone they don’t trust.

However, trust will naturally be built with a respondent as they pass through your survey and are less likely to drop out when they’ve put so much time and effort into responding.

It would be wise to save these types of questions for the end of your survey to increase completion rates.

7. Balance your scaled questions and provide a neutral answer options

For the best results, scaled question types should always stick to a certain formula. Firstly, your scale should be balanced.

If you have two positive answer options (e.g. Good and Very Good) then you should also have two negative options (i.e. Poor and Very Poor).

Bad example:

Very Poor | Good | Very Good | Excellent

In our example, there are more positive scale choices than there are negative. You can never be sure if a respondent who picked ‘Very Poor’ felt that strongly about the negative aspect of something, as there is no lesser option (i.e. Poor).

Also, respondents may tend to pick the negative option because the presence of more positive options makes it seem like they’re being led to one of those.

On top of this, each scale option should be the direct contrast to the one opposing it (e.g. ‘Very Poor – Very Good’ not ‘Very Poor – Excellent’).

Finally, always include a middle (neutral) option for Likert scales. These give respondents the ability to opt out of a question or statement if they don’t feel either positively or negatively about it. This ensures your results are as accurate as possible.

Good Likert scale example:

Very Poor | Poor | No Opinion | Good | Very Good

8. Ask "How?" instead of "Did?" in open ended questions

When asking about a respondent’s experience or opinion, how your question is framed will determine the quality of answer provided. For example, if you ask “Did you enjoy the event?”, then people are likely to respond with either “Yes” or “No”.

However, if you asked “How did you find the event?”, your respondents will provide more specific feedback, e.g. “Very informative” or “The presentations were a little long”.

Not enough info for you? Take a look at our article on how to create a survey that collects better quality data.